In 1900, Ban Johnson, the president of a minor league baseball league called the Western League, changed the name of his circuit to the American League and one year later obtained the status of a new major league to compete with the National League, founded in 1876.

One of its founding members, the Baltimore Orioles (no relation to the current Orioles), lasted only two years before struggling and limping through the end of the 1902 season and finally ceasing operations.

In 1903, the owners of the two leagues voted 15 to 1 to approve the sale of the defunct Baltimore Orioles to New York City businessmen Frank Farrell and Bill Devery for a cool $18,000. They dubbed their new team the Highlanders and spent the next twenty years playing second fiddle to the powerful and popular New York Giants.

By the time Jacob Ruppert purchased the club in 1915, they were known as the Yankees. Rupert was intent on building a powerhouse and when Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee began selling players to help finance his Broadway theater productions, Ruppert was a willing buyer.

The biggest of these acquisitions was a young star named Babe Ruth. When Ruth went to the Yankees in 1920, the whole baseball world changed forever.

On April 18, 1923, a 58,000-seat baseball palace called Yankee Stadium opened and Babe Ruth christened it with its first homerun – a three-run blast to right field. Yankee Stadium came to be known as “The House That Ruth Built.”

The Yankees would win their first of twenty-seven World Series championships that year and go on to become the nation’s most popular baseball team.

Despite all that history, I somehow became a Boston Red Sox fan.

My conversion date was October 22, 1975.

I had already considered the Red Sox for my favorite team and was nearly convinced while watching a replay of a particularly close game on the old NBC “Saturday Game of the Week” on television a few years before.

On a sunny summer afternoon, popular Red Sox left fielder and first baseman, Carl Yastrzemski, singled straight up the middle to center field.

Within a few seconds, Yastrzemski jumped off first base as the next hitter ripped a line drive, fair by inches, down the right field line. He gracefully rounded second, sprinted toward third, and was animatedly waved home by the third base coach.

My heart raced and chills went up and down my spine as Yastrzemski slid home in a cloud of beautiful brown dust—just ahead of the throw from right field and the tag by the catcher.

The home plate umpire leaned directly over the diving catcher, flinging his arms out to his sides to signal the safe call, and I knew I’d seen something of beauty. It was my first exposure to real art.

However, as any kid will tell you, sports conversions typically come as something of a magical moment—an epiphany, if you will. And so it was for me and the Red Sox on that fateful October night in game six of the 1975 World Series.

The Cincinnati Reds and their Big Red Machine of the 1970s came into the game leading the Red Sox three games to two.

As a result, game six at Boston’s fabled Fenway Park was do-or-die for the Boston Red Sox. Trailing 6 to 3, the drama began to unfold when Red Sox pinch hitter Bernie Carbo launched a three-run home run into the center field seats to tie the score in the bottom of the eighth.

As the ninth inning passed without a run, the game moved into extra innings, and the stage was set for what would be christened one of the greatest games in World Series history.

With the score still tied at 6 to 6, Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk walked to the plate just past 12:30 a.m. to lead off the bottom of the twelfth inning. Fisk stepped into the batter’s box, facing Cincinnati relief pitcher Pat Darcy before a sellout crowd waiting to erupt.

The first pitch, a ball, was followed by a low sinker. With a perfect-for-the-ages swing, Fisk hit a towering fly ball toward the left field foul pole and the lights over Fenway Park’s legendary left field wall known as the Green Monster.

The crowd roared and everything seemed to move in slow motion as the ball flew through the crisp, autumn New England night. As the ball soared up and out, it appeared to be headed for foul territory.

Fisk watched the ball in the air and, taking a couple of steps toward first base, waved both arms three times toward fair territory as if he had the power to control the wind.

Sheer pandemonium erupted and Fisk jumped all the way to first base as the ball grazed the foul pole—fair by inches—and flew over the wall, off the screen above the Green Monster, into history, and into my heart.

With one now-famous swing, the Red Sox had tied the Series. And even though the Red Sox lost the Series in game seven, my epiphany was complete: I was an official Red Sox fan. To this day, I still see Fisk in my mind, dancing toward first base, waving that ball fair.

My dad, on the other hand, was a New York Yankees fan. Anyone who knows of the heated Yankee–Red Sox rivalry knows the profound significance of that statement. Nothing more can really be said.

But there was no malice on my part, no desire to go against the grain; it was one magical swing by a catcher named Carlton Fisk.

To my dad’s credit, he gracefully accepted my position. Who knows how these things happen, but I’m sure my dad wondered where he went wrong. He did seem more vigilant about my upbringing after that.

Rivalry aside, it was my dad who first endowed me with the love of baseball.

He was my first hero.

A good ballplayer in his own right, he threw me my first ball and was my first little league coach.

He grew up listening to the Yankees on the radio from tiny Castle Dale, Utah, and was raised on a strict diet of players like Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle, and the great Yankee teams of the late 1940s and 1950s.

With those great lineups, who could blame him for being a Yankee fan? He always told me that the feuding Yankees of the late 1970s soured him, but I knew, deep in his heart, dad was still a Yank.

Years later, after converting my wife and our six children to my beloved Red Sox, child number seven came along and I knew he would follow in the footsteps of his baseball crazy clan.

He was given all the trappings fitting for a new Red Sox understudy – onesies, bibs, rattles, bottles, a hat, the works. He was surrounded by the influence of Boston Red Sox books, framed photographs, and the daily dinner table banter about box scores and up and coming minor leaguers. Train up a child and all that jazz.

He had it all. Then he didn’t.

One dark weekday, when my wife was helping at his school, she met a woman wearing a Red Sox hat and entered that solemn repartee of all fans who share a passion.

“We’re all Red Sox fans”, my wife proudly stated. A few minutes later, little kindergartner Joseph uttered the unimaginable.

“Mom” we’re not all Red Sox fans” he said.

“Who isn’t,” my wife asked. Joseph replied, “I’m not.”

My wife then said, “Who do you like?”

Then came the blow. “The Yankees.”

He could have said the Dodgers because of proximity or the Royals because he liked the water fountains in center field.

But no, he swung for the rival fence and, in the process, tossed the piercing end of his splintered baseball bat right through my heart as he jogged around the bases.

I was stunned. How did this happen?

I called my dad. He laughed and then said “Gotcha!”

As George Abbott and Douglass Wallop said in their musical comedy of the same name, “Damn Yankees.”

Over the course of time, I have adjusted. I resisted the urge to sell him to some passing gypsies; after all, I had grown very fond of him.

Joseph and I have found the common ground we share of the game itself and the creation of an internal family rivalry has brought some excitement and stoked the competitive fires.

In a weak moment a few years ago, I promised Joseph that, just as we had visited Fenway Park to see the Red Sox, he would get to visit Yankee Stadium.

I have plenty to be proud of when it comes to Joseph. Born with a life-threatening diaphragmatic hernia (a hole in his diaphragm that allowed his abdominal organs to move into his chest cavity so his lung could not grow), Joseph underwent surgery on day two of his life and spent three plus weeks in the hospital.

Our prayers were answered when he came home.

Today, you would never know he had the defect unless you were to see the scar on his stomach.

Five months ago, Joseph suffered another injury.

When a friend climbed on top of a vending machine and then couldn’t get down, Joseph climbed up to help him. When he himself jumped down, he caught the ring finger on his right hand on the hinge and pulled his finger off.

It was a complete de-gloving, and he lost the finger at the knuckle. At a time when he could have experienced feelings of doom and self-pity, Joseph received strength from on high and used his sense of humor and positive attitude to bravely move forward.

He happily takes each day and has been an inspiration to so many people.

On the day of his injury, he happened to be wearing his New York Yankees sweatshirt. When the nurses prepping him for surgery couldn’t pull it off over the bandages, they told him they would need to cut his sweatshirt from bottom to top.

My quick response was “I’ll get the scissors.”

Joseph classically said, “Forget about my finger; save my Yankee sweatshirt!”

With that in mind, my wife and I decided now was the time to take our three youngest children on a trip to New York City followed by visits to upstate New York and Ohio to visit historic sites of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I thought what better way to cleanse my soul from Yankee Stadium than a trip to Mecca so to speak. It was either that or find an exorcist. I opted for Palmyra and Kirtland.

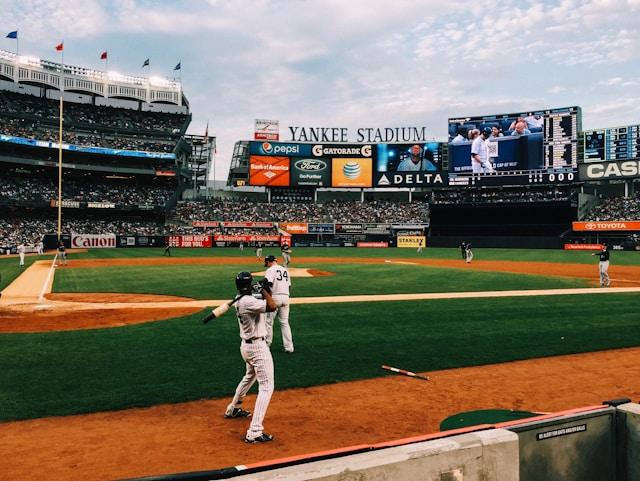

So, on June 5, 2024, I went to Yankee Stadium.

We boarded the Number 4 subway train at Grand Central Station for our pre-game tour and disembarked at 161st Street, right across from the replacement of The House That Ruth Built. I must admit, the whole thing was impressive.

A grand, off-white palace, reminiscent of the original, stood stately and imposing and the Yankee’s Museum and Monument Park inside told the tales of championships and hall of famers galore.

Then came the game and, much to Joseph’s delight, the Yankees scored four runs in the first inning and disposed of the Minnesota Twins handily 9 to 5.

Rivalry aside, it was a wonderful day and a wonderful trip.

JoAnn and I have found that family vacations, large or small, near or far, provide great opportunities to bring family close together and create priceless memories.

As for Yankee Stadium, it was a great connection to my son on one side, and my deceased father on the other.

My dad, the greatest man I’ve ever known, had such a profound influence on my life.

When I wanted to learn to play baseball, I began to practice in our backyard where I faced the imposing brick wall of the back of our garage.

Our garage was connected to the end of our house and had a raised cement patio that separated it from the expanse of our back lawn. It was here where I became a baseball player.

Day after day, week after week, month after month, and year after year, I threw balls at that brick wall under sunshine, shade, clouds, rain, and even snow.

Over the years I played countless full-length games and created my own fantasy leagues long before they were in vogue.

I memorized statistics, replayed history, and learned the ins and outs of America’s pastime. Throwing against that brick wall became more than practice.

It was therapeutic; it was a place where I witnessed my own improvement, and it was a symbol of my happy childhood.

It was also the place where my dad—through action, not word—taught me about priorities.

The spot on the lawn where I threw from quickly succumbed to my daily baseball battery. The remaining dirt sunk a few inches and hardened.

The better I became, the farther I stood from the garage wall, expanding my “pitcher’s mound” to roughly fifteen feet long by five feet wide.

Over the course of a few weeks, dad’s beautiful green oasis developed a stark, parched sinkhole that looked like an industrial holding pond during rainstorms.

But through it all, my dad never said a word. Regardless of the horror expressed by many (“Duane, what happened to your lawn?!”), he simply smiled and watched me play.

My dad knew how important it was to me. He not only knew that I wanted to become a better baseball player—he wanted to let me learn how to persevere. Through it all, I became a better baseball player.

But more importantly, my dad taught me about priorities as I learned what his were. He showed me that I was far more important to him than a nicely groomed back lawn.

Hopefully, my sincere actions with my children have shown them they are the most important thing to me. Joseph knows that he and I share a love of baseball and that I am proud of him.

He also knows he is far more important to me than the Boston Red Sox.

In 1941, Grantland Rice, an influential sportswriter from the early to mid-1900s, wrote a verse fitting for both sports and life.

It perfectly describes the great man who is my father as well as the greatest lesson he ever taught me about focusing on what matters most.

It also reminds me of who I want to be.

The illustrious Rice wrote:

For when the One Great Scorer comes to mark against your name,

He writes—not that you won or lost—but how you played the Game.

Read more stories like this and learn valuable lessons from the book Fatherhood: The Role of a Lifetime. Available now on Amazon!